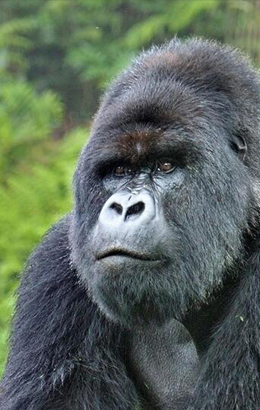

Solitary silverbacks, the bachelors of the forest

Hi, this is Tuver in Goma,

When you think of a silverback, you almost certainly think of a powerful adult male gorilla leading and protecting his family. And, well, you’d be right – to an extent. You see, not all silverbacks are leaders, and not all of them live in groups. In fact, right now there are probably more than a dozen mature male mountain gorillas wandering through the forests of central Africa. Understanding why they’re alone is key to gaining a full understanding of the complex social life of our closest cousin. Let me explain…

A male gorilla will usually start growing distinctive grey (or ‘silver’) hairs on his back and shoulders aged between 11 and 13. By now, he will be almost fully grown and physically very impressive. Inevitably, his thoughts will start turning to starting a family of his own, even if this means he will have to fight an older silverback for dominance of his group.

In most cases, while they may have the desire to launch a forest coup and take over as alpha male, at this point in their lives, they simply aren’t strong enough to beat the reigning silverback in a fight. They are, however, a concern for the alpha male, so it’s in both parties’ interests that the younger silverback leaves the group.

On his own, a silverback will wait for an opportunity to persuade females to join him

Solitary silverbacks can spend many months, even years, living on their own. In fact, relatively little is known about their lives since, unlike groups, they are hard to find and study, with researchers or rangers often coming across them deep in the forest almost by chance. What is clear is that they use this time to grow in size, strength and confidence.

Before long, a lone silverback will start looking for chances to either start a group of his own or take over an existing family. Often, they will latch onto a group, following them at a safe distance for weeks or even months in the hope of attracting the attention of one or more females.

If this works – and it occasionally does – the females will simply leave their group quietly, going off with their new leader to start a new family. This, of course, is the most peaceful outcome and usually only occurs if the alpha male of the group being stalked is old or weak or if the family is simply too big to govern effectively.

Alternatively, a solitary silverback will simply bide his time. Many gorilla families are led by a single silverback and when he dies, the females, as well as juveniles and adolescent males, will need a new leader. Then it’s just a matter of winning over this group, for instance through displays of strength such as chest-beating or mock charges.

What is interesting is that actual aggressive takeovers are almost unheard of in the gorilla world. Certainly, in many other primate species, adult males will fight it out for control of a group, often to the death. However, it’s important to remember the influence adult female gorillas hold over group dynamics. Quite simply, if they don’t like a male, they won’t consent to being led by him. So even if a silverback did take a huge risk, fight a rival and win control of a group, if the females didn’t like the look of him, they would simply walk away.

But how successful is this tactic of going it alone and waiting for a chance to present itself. According to some recent studies, only around half of all solitary males go on to have offspring of their own. This might be why some male gorillas prefer to stay put and be subordinate to a silverback, a tactic that would also offer greater protection against predators such as leopards.

However, as I said, compared to what we know about gorilla groups and silverbacks in such families, relatively little is known about solitary males, including what makes them choose to leave in the first place. Hopefully, as GPS technology makes finding and tracking such individuals easier, this will slowly change and we can come to learn even more about the behaviour of these fascinating great apes.